Sometimes it seems that the most urgent issue today is the power and influence of social networks. No longer are they only a vehicle for communication between and among people; they are so influential that they can determine the results of elections, destroy businesses, and invade the privacy of every individual. We spend so many hours on Facebook, Twitter, Google+ and others that a substantial part of our life experience take place in a virtual space. Some people expose their private lives, others only share articles and photos. Be that as it may, we can no longer deny that the line we draw between life in reality and virtual life is of great importance.

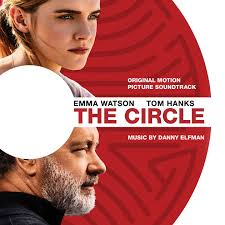

The film The Circle (2017) takes place in a high-tech company called The Circle, which operates in social networks and puts one in mind of companies like Google or Apple. The protagonist, Mae Holland, comes from a lower-class family; her father is ill and her mother looks after him. With the help of a friend, she manages to get a job at The Circle. She takes the opportunity to advance professionally and to improve the economic condition of both herself and her parents. As an employee, she is caught drowning by a company security camera, and the Coast Guard rushes to save her life. Mae is fully persuaded that documenting life with a camera is beneficial. In a meeting of the boss with all company members—who faces his employees is a way that truly reminds us of Steve Jobs—she is asked to be the first “fully transparent” employee: she will carry a small camera that will constantly air her life, where she is, what she sees. She agrees because she feels transparency is beneficial and the company is struggling with corrupt politicians. The boss adds that his son is confined to bed, and if he sees Mae’s life he could “participate” in activities he is unable to do. Mae carries the camera, but due to some malfunction she sees her parents having sex and the scene is shared with whoever is following her. This is the first of many negative repercussions.

In the next company meeting, Mae addresses the workers, saying that the company’s software can find any individual—including fugitives—upon the earth within twenty minutes. Someone suggest she find her childhood friend, as people are angry with him. Mae had shared his lamp made of deer antlers, and her animal-activist friends are sure he hunted the deer to make the lamp. The software finds him, yet chasing—hunting, really—him leads to his death. Broken-hearted, she leaves the company but later returns, in spite of her parent’s objections. Eventually, she makes the bosses become “transparent” as well, albeit against their objections.

The explicit issue of the film is the controlling power of technology. Some people are willing to be “transparent,” and others prefer the shadows, taking advantage of their positions for manipulation and profit. From this respect, the film is rather banal, as some critics have point out. Obviously, we don’t want “big brother” to follow us or run our lives. We all want a balance between useful technology and individual rights.

But, implicitly, the film deals with an altogether different issue: self-consciousness, perception of the “self,” an understanding of what an individual is, where she or he begins and ends. Philosophy has always discussed this question. In a wider context, the philosophy of the “self” asks the fundamental question: What makes a person separate from the environment? It could be argued that the “self” is an entity consisting of thoughts, emotions, and life circumstances; a person is an autonomous complexity. We relate to the world around us but exist independently. Each and every one of us is a distinct person, even if we are influenced by people, ideas, and feelings. In simpler words, we could ask: Where do I exist, me and no one else, and where do I mix with the world around me, to the point that I am not sure if I see and feel myself or others?

Western philosophy has discussed this question from antiquity. Aristotle claims that man is unable to perceive his surroundings without self-awareness. It is impossible to comprehend the world without acknowledging your own “self.” In the Middle Ages, the philosopher Avicenna argued that even if the human soul were completely detached from its senses, it would still entail an enduring element of self-consciousness. Man knows he is separate from his environment, even if he is unable to see the dividing line. Thomas Aquinas asserted that human thought—the mind and not the senses—was the source of self-consciousness. In the seventeenth century, at the dawn of the modern age, Descartes said, “I think, therefore I am.” That is, I know I exist but I doubt everything else. It was the twentieth century that undermined the belief that man has an intuitive perception of himself versus the world. “The ‘self’ is like an eye that sees everything but not itself,” said the renowned philosopher Wittgenstein, and Sartre stressed the importance of memories in self-perception: If all my memories had been erased, would I still be me?

The Circle discusses the implications of the “self” in the context of social networks. Mae Holland is willing to carry a camera and thus enable whoever is following her to see what she sees and take part in her experiences. And so, the line between her “self” and the other members of the network is partially erased. Each and every one can look at the world through her eyes; the only exception is nudity.

It is interesting that Mae doesn’t refute the fact that the camera deprives her of part of her “self”. At first, she is embarrassed. Then she feels she serves a worthy cause—it’s worth giving up a part of yourself for a world with no corruption. At the next stage, she finds that blurring the dividing line may be catastrophic. What we find positive may become negative in the minds of others. But, as she mourns her friend, she feels the virtual support is very encouraging—apparently, giving up part of yourself generates empathy. Eventually, she comes back to her belief in full transparency, but only if everyone is equally exposed.

An interesting topic, so relevant to our world.

Leave a Comment