Some children’s books are unforgettable. Perhaps it has to do with them articulating life’s most fundamental questions in a clear and vivid way. The best ones implant an idea in the child’s mind, which then evolves and deepens over the years, long after the book was read. For me, Erich Kästners’ Lisa and Lottie is such a book. I feel that the way it deals with the various aspects of identity sparked my own interest in the ‘self’.

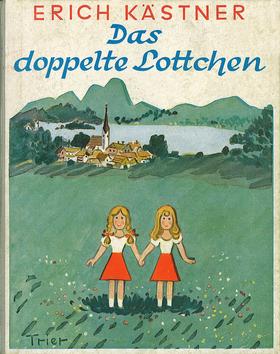

The German writer Erich Kästner (1899-1974) was a pacifist and an anti-Nazi. He began writing Lottie and Lisa (Das doppelte Lottchen (“The double Lottie”), the film The Parent Trap was an adaptation of the book), in 1942, concluding it in 1949. He remained in Germany during the war, writing apolitical books under a pseudonym. Das doppelte Lottchen was published in 1949, immediately becoming a best seller.

The plot is captivating and highly original: two nine-year-old identical twin girls, Lottie and Lisa, were separated at infancy. When the parents divorced, each kept one of the girls. Lisa grows up with the father. She is spoiled, naughty, daring and aggressive. Lottie is brought up by her hard-working mother. She is shy, tidy and responsible, an excellent student, and she practically manages the household. They are both unaware that they have a twin sister, or of what exactly happened to the parent who isn’t raising them.

By chance they are sent to the same summer camp. Of course each one is shocked to see another girl looking exactly like her. At first they dislike each other but soon an intimacy is created, and they find they are indeed twin sisters. Together they plot to trade places after the summer, so Lottie will get to know her father and Lisa her mother: “they will exchange clothes, hairstyles, trunks, toys, characters, and private lives!”

When the camp is over Lisa travels to Munich, pretending to be Lottie and Lottie travels to Vienna, pretending she is Lisa. The reader follows them curiously, wondering if they will be able to live each other’s lives. Will the wild Lisa be able to be moderate and responsible, cook and be a model student – and will her shy, inhibited sister be able to be mischievous, bold and assertive? And will the parents notice any change in their characters?

Well, the girls fail to adopt each other’s natures. Both parents observe the change, but don’t suspect anything. And so do their teachers: “Weeks had gone by since the twins changed places … Lisa had “again” become an expert cook. The teachers in Munich got more or less used to the fact that the little Horn girl had come back from her vacation less industrious, less tidy and attentive but, on the other hand, more lively and quick on the uptake. And the teachers in Vienna were quite pleased to find that Conductor Falfy’s daughter worked harder in class and was much better in arithmetic.”

Naturally the book has a happy ending: the parents find out that the girls changed places, and this eventually leads to their reuniting and remarriage. But the heart of the book is the implicit discussion about selfhood: is it possible to take the place of another person without anyone knowing it; what people expect of a person vs that person’s character; and the validity of stereotypes. It could even be argued that the book implicitly deals with the question of genes versus environemnt. It is implied that since the girls are identitcal twins, their different character is a result of their upbringing. The girl who grew up with a male parent in an affluent environment develops is a completely different way than the one growing up with a female parent, in a home with economic hardship.

As a child, I used to wonder what would happen if I were to be placed in new, unfamiliar circumstances – would it be a fresh new start: would I be an entirely different person, the one I wanted so badly to be, or would the same ‘me’ pop up? We expect children’s books to stimulate a change, to make the young readers believe it is possible. Surprisingly, unlike most children’s writers, here Kästner lacks a pedagogic message: already at the age of nine a person’s character is well-defined and she is unable to change. Though each girl tries to adopt the character of her sister, they both fail.

The readers are driven to contemplate his or her own situation. If they suddenly behaved differently, how would their family, friends, and teachers react? Would they see it as a positive on negative change? As one would expect, ‘Lisa’’s friends and teachers are happy with her changing into a more serious and attentive girl. We all know society encourages children to excel in school and be well-mannered, even at the cost of their freedom of spirit. But what happens when a well-behaved girl turns undisciplined and wild? This is far more interesting!

‘Lottie’’s teachers complain, her friends like her vividness but resent her aggressiveness, yet her mother has interesting insights. First, she blames herself. Later, talking to the teacher, she argues: “I want Lottie to be a child and not a stunted little grownup! I would rather have her a happy, genuine little girl than forced at all costs to be your best student.” Thus, she explicitly juxtaposes excelling in school and happiness.

I love Lottie and Lisa because it both portrays the harsh realities of life and criticizes them. Society pushes us to act in a certain way; yet in doing so, we abandon some of our inner freedom. Conformism is very useful, but it has an element of self-destruction.

I would like my children to be equipped with this understanding.

Thanks, I will definitely watch “Three identical Strangers.

I love Lottie and Lisa. It was very interesting to read it again, as an adult and a mother.

Many thanks.

This is very interesting. On Netflix at present, you can see a documentary “Three Identical Strangers” – fascinating and disturbing. The tentative conclusions it reaches do not, it seems to me, introduce all the possible factors.

Many thanks for this commentary on a book I loved as a child.