Many interesting and impressive women took part in the Zionist struggle, but only a small fraction of them found their way to history books. These are full not only with leaders and brave soldiers but also with some wheeler-dealers. Unfortunately, the names of some worthy women were overlooked, in spite of their contributions to society.

Sarah Thon (1881-1920) was born in Lemberg, then Galicia, to a family with feminist principles. Though the family was poor, she attended the first school for girls in the city and excelled in her studies. In 1903 she traveled to Berlin, where she met her husband, Jacob Thon, a Zionist leader, and together they moved to Palestine. The family was struck by misfortunes; three of their five children passed away at a young age, but the couple kept up their public activities, which may have provided some comfort.

Sarah felt that promoting women in the new Zionist society was her calling. Already in Germany she joined the ‘Women’s Organization for Cultural Work in Palestine’, and was determined to improve the condition of women in the new society. The Zionist movement at that time had an ambivalent attitude toward feminism. On the one hand, many saw the profound change in the life of the nation as an opportunity to create an egalitarian society, to make women equal partners. On the other hand, the spirit of early Zionism reflected the common views at the time – voting right was granted to women in the UK and US only in 1918 and 1920, respectively. In the first decade of the twentieth century, some still believed feminist ideas to be false and detrimental to society. Sarah engaged in activities for the benefit of women, certain that equality between the sexes would create a more prosperous society; women working and sharing the burden of society would most likely engender prosperity.

The economic conditions in Palestine in the second decade of the twentieth century, and particularly during WWI, were catastrophic. The land was struck by famine and plague. Many Jewish donors couldn’t support the new society anymore, and the Othman government deported ten thousand Jews from Tel Aviv, suggesting this would somehow protect them.

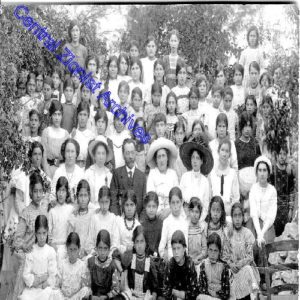

This era and its social implications are not often discussed; the economic situation forced Jewish girls from respectable families to resort to prostitution. The conditions were so harsh that they were willing to do anything for the survival of their families. Sarah established an organization to support the deportees. But in order to keep the young girls from prostitution, she decided to provide professional education. She established a school for handicrafts, teaching girls of various ages to lace, embroider and weave.

Today, one can appraise the level of equality between men and women by examining the professional choices made by each. Feminists encourage women to engage in occupations perceived as “masculine”. But one has to remember that one avenue women took to advance towards economic equality was building by of “feminine” professions. Estee Lauder sold face creams and grew an economic empire; Martha Stuart turned home management into a prospering brand. From this perspective, making money is more important than the choice of occupation. Sarah thought that if the girls could earn some money from embroidery they would become equal members of family and society, and then they could turn to other professions.

It is a well-known fact that early Zionists ascribed a unique role to agriculture, and the “New Jew” was expected to be person working the land. Sarah supported the establishment of the Young Women’s Farm (discussed in this blog), and helped find donors to support it. But as she visited the farm, she was surprised to learn that the women didn’t clean the kitchen, they hardly washed themselves and they cut their hair short and avoided any feminine care. They felt that equality actually meant resembling men. Sarah strongly opposed this. “Their drive to be equal to men makes them stop caring for their appearance, they cut their hair and intentionally remove the graceful mystical thread stretched along any young woman’s face.” Here, also, she was ahead of her time. Contemporary feminists often discuss the difference between equality and similarity, arguing that women wishing to be equal members of society don’t necessarily need to adopt a masculine model. Sarah had profound reservation about the girls’ attempt to look like men. Woman’s self-value should not rely on her looking like a man but rather on her achievements as a woman. Her position might have also stemmed from her urbanity. Zionist ideology made her support women engaging in agriculture, but she was inclined to city life.

Sarah Thon brought women organizations together. In various places around the globe, women realized they couldn’t act alone against discrimination—the only way to progress is by joining forces. Sarah invested many efforts in establishing a Zionist women organization; In 1919 the General Women’s Movement had been established. She wanted to be elected to the first Jewish National Council in 1920, but she died of malaria three weeks before the election. The words “The Founder of the Jewish Women Movement for Equality in Israel” were inscribed on her grave.

Leave a Comment