Jesus in Israeli Literature II

In the decades since the formation of the State of Israel, a slow and gradual change has been taking place in the attitude of Israelis towards Christianity. When the country was founded, the memory of being a persecuted minority in a Christian world was vivid in the minds of many; large numbers of new immigrants bore the trauma of the Holocaust. Thus, Christianity was seen mainly as an anti-Semitic phenomenon, and teaching it never became part of high school curriculum. Today the Christian world evokes some antagonism perhaps – but mainly increased curiosity.

A.B. Yehoshua (1936- ), a well-known Israeli author, exemplifies this change. Born in Jerusalem to a Sephardic Jewish family that has lived in the city for five generations, he served as a paratrooper in the IDF, studied philosophy at the Hebrew University, and later became a literature professor at Haifa University.

In 2004 he published a novel titled A Woman in Jerusalem. During the second Intifada a terrorist explodes himself in the central Jerusalem food market. An anonymous woman is brought unconscious to the hospital on Mt. Scopus and dies after a couple of days. Her body lies nameless in the hospital morgue. Strangely the body is intact, except for wounds in her palms and feet and a scratch on her forehead. A local reporter learns that she used to work at a big bakery in Jerusalem. The owner, publicly criticized for not taking care of a wounded employee, is unable to find any record of her employment. He orders the human resources manager to find out who she was, and when the bakery had employed her.

The reader becomes part of the human resources manager’s efforts to reveal her life circumstances. Yulia Ragayev, a woman about forty years old, came from the Former Soviet Union to live in Jerusalem. Her partner and a son left Israel as the threat of terror grew, yet she was determined to stay.

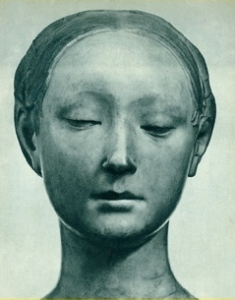

Yulia was an illuminated person, charismatic in an introverted manner. Not exactly beautiful, not very sociable, yet there was something about her that made everyone love her. The night-shift manager at the bakery was touched by this foreign worker; thinking that a delicate woman like her shouldn’t be working at cleaning, he sent her off to find another job, without letting anyone know. She lived in a shack in an ultra-religious part of Jerusalem, and was loved by the people there “even though she wasn’t Jewish”. The doctors at the hospital were attached to her, in spite of her being unconscious. And the human resources manager became captivated by her image after her death, feeling she might emerge any minute now, alive and well. Her unique nature is emphasized by the fact that she is the only character who has a name.

The owner of the bakery, feeling guilty for not visiting her at the hospital, decides to have her buried at home, in her village in Eastern Europe. So begins a long, hard journey. The human resources manager, the reporter, her son, her ex-partner, and other people, all join in accompanying Yulia on her way to her burial.

After overcoming endless obstacles, they finally reach the remote village in the high mountains. Her mother returns from a short stay at a convent, wearing a nun’s robe. Learning that her daughter was brought to be buried there, “the old woman reacted like a wounded animal […] she threw herself at the human resource manager’s feet, pleading that her daughter be returned to the city that had taken her life. That way, she, too, the victim’s mother, would have a right to it”. The human resources manager, now fully absorbed by the character of Yulia, accepts the mother’s wish to take the body back to Jerusalem.

A.B. Yehoshua’s way of familiarizing the reader with the Gospels is by dismantling the passion of Christ, and then embedding various elements in present-day Israel. The illuminated character, here a woman rather than a man; the wounds, which resemble those of the crucifixion; the days the body lies not in a cave but in the morgue; the journey of the disciples; a via dolorosa; Yulia’s preferring her religious belief over being with her family; the route to Jerusalem; the sensitivity to society’s weaker members – all reflect Jesus’s life and death, yet A. B. Yehoshua has planted them in a new, modern story. In doing so, by no means is he voiding them of their spiritual meaning; on the contrary, they become more tangible, easily appreciated by the Israeli reader. The story of Yulia Ragayev’s life and death is about piety, grace, and generosity; it has nothing which provokes antagonism.

And there is Jerusalem. In the midst of the bloody Arab-Israeli conflict and the struggle between Jews and Muslims over the city, A. B. Yehoshua reminds us that millions of Christians see it as their own – not in a political sense, but in a fundamental spiritual way. Whoever rules the city, should always keep this in mind.

For the first post on Jesus in Israeli Literature, click here.

For the third post on Jesus in Israeli Literature, click here.

There are certainly plenty of extremists in this neighbourhood!

It is a very interesting novel, with many subtleties I couldn’t descibe in he post.

We hear so much about extremists, both in Israel, the U.S., and everywhere, really, that this essay’s tone of reasonableness is most welcome. I was not aware of the novel you discuss and find myself wanting to read it and to learn more about it.